Unstable editions of Ortelius' atlas

by Marcel P.R. van den Broecke

The author is a scientific adviser and Managing Director of the Company Cartographica Neerlandica in Bilthoven, the Netherlands which specialises in maps of Ortelius.

Abraham Ortelius as depicted by Paul Rubens (1577-1640). (By courtesy of the Plantijn-Moretus Museum of Antwerp, where the original is displayed).

Abraham Ortelius'monumental work Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is regarded as the first atlas to appear. An atlas is defined in this instance as a uniform collection of map sheets of similar size, with sustaining text, compiled for the purpose of binding the sheets together to form a coherent book.

The Theatrum was an instant success and four issues of the first edition were published in 1570. When it appeared, it was the most expensive book ever printed. Despite this it was received by the public with such enthusiasm that no less than 7300 copies were produced in thirty-one editions from 1570 to 1612.1 Ortelius also issued about 750 copies of Additamenta and about 600 copies of the Parergon (maps from the antiquity), some separately, some bound up with the regular atlas to order. Ortelius is often characterised as being merely a publisher and compiler rather than a cartographical innovator but recent research by Peter Meurer2 has shown that the innovative nature of the form and content of the Theatrum should not be underestimated.

At least 900 copies are known to have survived to the present day,1 and there may be more because libraries, particularly in Eastern Europe, are still finding previously unrecorded copies. To obtain a better view on the question of how issues of the Theatrum relate to what is commonly regarded as an edition of an atlas I examined different copies of one edition and this research convinced me of the necessity to introduce the concept of unstable editions.

Throughout the various editions of Theatrum there are 228 different plates, 174 in the regular atlas editions and 55 in the Parergon. In spite of numerous attempts over the past century to establish a definitive list of plates, new ones are still being identified: since publication of Peter Meurer's book2 in 1991 and Robert Karrow's book in 19933, Meurer has found plate 71/II 'Hannonia' 1575, and I have found 93/I 'Americae' 1579-84 (Meurer's 93/I 'Asiae'should be renumbered 71/I as this plate does not stem from 1579 but from 1575), 93/IV 'Valentiae', 116/I 'Angliae, Scotiae et Hiberniae' 1589, 135/VI 'Palestinae' 1595-1612, 33P/II 'Italiae Veteris' 1595-1624 and 39P/IV 'Erythraeae' 1609-1624. The first edition of 1570 contains 53 plates. the largest edition of Theatrum, the English edition of 1606, contains as many as 166 of the total 228 plates; 29 are from the first edition. Clearly, many new plates were introduced and only a few cast aside. An up-to-date inventory of plates is given further on in this article.

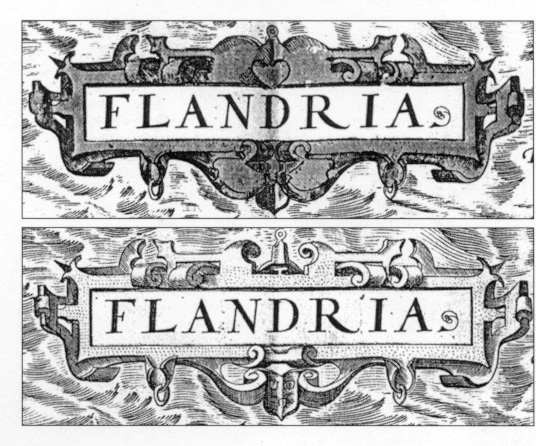

Two states of the cartouche of the Flandriae plate,occurring in two exemplars (Leiden University and Amsterdam University) of the first version of the first edition of the Theatrum, (Koeman's Ort 1A). The Leiden exemplar shows a heart, the Amsterdam exemplar does not.

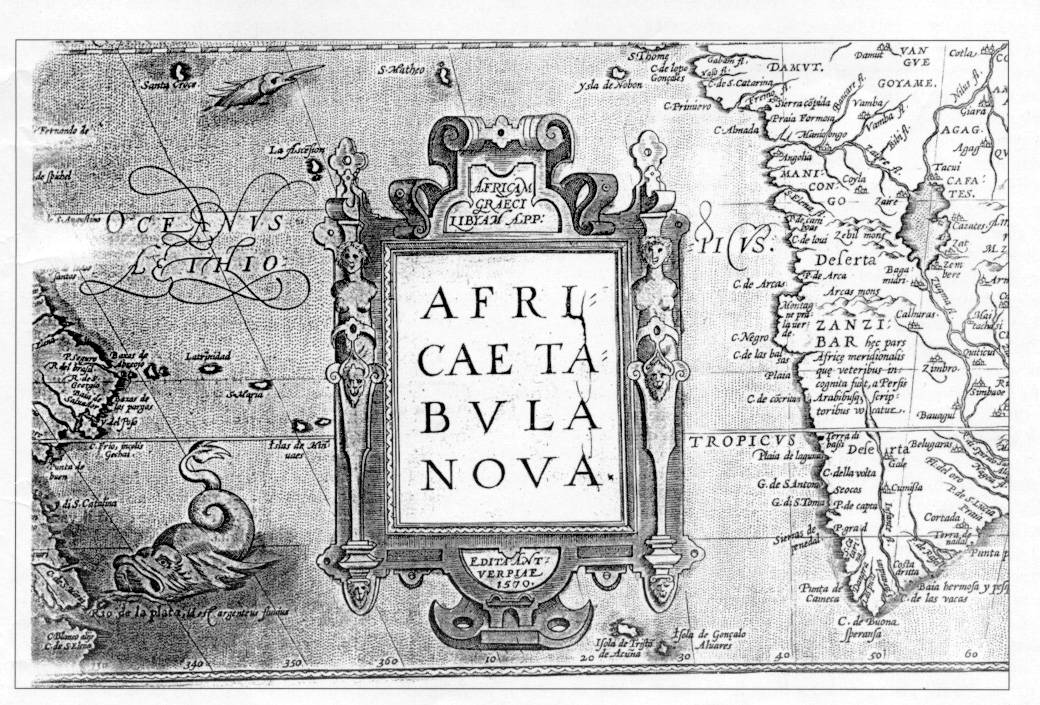

An "unintended" state of a map in the form of plate damage can also help in determining its age. In this case plate damage consists of a crack which began to form in the cartouche of the continent map of Africa after 1602 and which progressively widened with each subsequent edition. This is what the cartouche looks like in the editions of 1612.

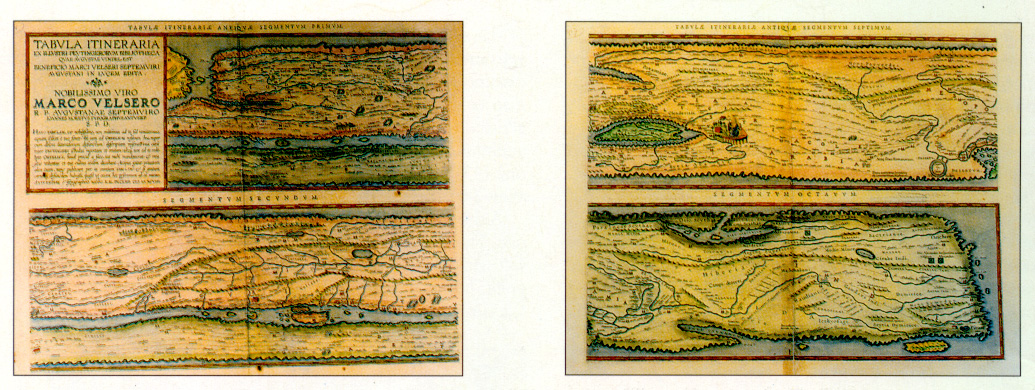

As a true humanist and renaissance cartographer, Ortelius was keenly interested in the geographical knowledge of classical antiquity. The Parergon maps, which he considered his major cartographical achievement, bear witness to this. As early as 1578, Ortelius knew about the existence of the Peutinger tables and tried to get hold of them. They show the Roman world view around the third century. The original, found by Konrad Celtes (1459-1508) in a library in Augsburg, came into the hands of Konrad Peutinger (1465-1547) and later went to his relative Marcus Welser. Welser was the first to publish a copy of it in 1591 at Aldus Manutius in Venice, which Ortelius possessed but found inadequate and insufficient, since it seemed to deviate in many respects from the original. In 1598 new, more accurate copies were made by Welser at Ortelius'request. These formed the basis of his Peutinger tables in four sheets. Proof prints from these plates went back to Marcus, were compared with the original and corrected accordingly. The original Peutinger tables disappeared, were found back in 1714 and are now in theNational Library in Vienna. Because of damage and progressive blackening of colours of the 11 (once 12) original sheets of parchment, together once forming a roll, Ortelius' version now is the most reliable representation. Ortelius supervised the engravings but did not live to see the final result, which was first published by Moretus in 1598 as a separate booklet with text by Ortelius. Subsequently, Bertius included prints from these plates in his Theatrum Geographiae Veteris without text. It was not until 1624 that the tables finally appeared in the last edition of Ortelius' Parergon, produced by Plantijn-Moretus. To demonstrate the importance Ortelius attached to these tables, consider his final piece of text accompanying them (translated from Latin): "Farewell dear spectator and dear reader, enjoy this monument which, although it has plenty of shortcomings, does not have an equal or even anything like it under all the relicts from antiquity".

The sheets form a road map. The North-South dimsension is heavily crushed. The first segment begins with England and Spain. Most space and greatest accuracy is devoted to Italy and Greece (segments 2-5). The Roman world ends in the east with the river Ganges and island of Ceylon. Shown here are the first and last segment.

The first and most obvious reason for discarding a plate and replacing it with a new one is increased geographical knowledge. Knowledge of the world expanded at a tremendous pace during the life cycle of the Theatrum and examples where incorrect information leads to correction by introducing a new plate are plentiful. The bulge on the west coast of South America on plates 1 and 2, corrected on plates 113 and 114, are the best known examples but there are others, even among the Parergon plates.1

The second reason for introducing a new plate also goes back to increased knowledge. Whereas Ortelius had insufficient information (and perhaps insufficient economical resources) to include a map of the Pacific or Japan for example, the commercial succes of the atlas and the information he obtained from new sources warranted later inclusion. Uncertainty about the reliability of existing maps also led him in various instances to add another map of the same region, often with different information. This allowed the user to choose which map was more pleasing. The addition of a second map of Hungary (91) next to the exisitng one (42) is an example of this, as both plates continued to be altered during their life-cyrcle.

A third reason for introducing a new plate was wear of the old one. The second plate of the world map (112/I), replacing plate 1, still with the bulge in the South American coastline, is a case in point. From 1575 onwards, plate 1 developed a crack in its lower left corner and the bolts applied to keep it together were only a temporary solution.

Finally, there is a mystery category. It is unclear why a new Abraham plate (25P/I) was made next to the old one (12P) since they were used side by side for some time. They differ mainly in the diagonal direction of the background hatching and must have taken a great deal of time and effort to engrave due to the delicacy of the scenes in the twenty-two medaillions surrounding the map. Maybe the plate was lost for a time.

Then there is the matter of copyright or privilegio. An older version of 'Artois' (map 82) was reintroduced at a later stage, when a newer version (map 115) was already available. This had to do with privilege as indicated by Denucé4. Some offprints of this map were included in the Latin edition of 1575 in the expectation that privilige would be obtained from Philip II but when it was refused a new version was made. When the privilege was finally granted, the old plate reappeared. Finally, as Meurer points out, there may also have been parallel printing of nearly identical plates on different presses to speed up production. Homann at one stage employed three plates for one map in parallel. These prints can be distinguished only by differing widths between the edge of the print to the edge of the platemark.

No systematic, exhaustive attempt has so far been made to identify the various states of each of the plates and it is beyond the scope of this paper. However, on the basis of meticulous inspection of various copies from a few plates in different editions (such as plates 41, 42 and 43 by László Gróf5), plate 18 'Zeelandicarum' by Frans Gittenberger (unpublished), plates 1, 112/I, and 113 'Typus Orbis'6 or plate 19 'Hollandiae' in my paper1, it seems fair to assume that all plates except the very shortlived ones existed in more than one state. This is understandable as copperplates wore out quickly and needed recutting after 1000 impressions. Some had even shorter lives giving only 300 impressions. Correcting a plate was obviously more economical than replacing it.

In addition, there are also different variants which resulted from damage to the plate (see letter from R. Shirley to the Editor of TMC about definition of state. Issue 67, p.56). The first plate of the world map is a case in point; in 1575 its lower left corner broke off. An engraved copperplate took two to six months to engrave it represented a considerable investment and could not be easily discarded. Therefore, copperplates were repaired whenever that turned out to be feasible. The world map plate was repaired by bolting a sustaining piece of copper to the back of the plate. An image of these bolts can be seen in the impresiions and help identify the version. Shirley7 and personal communication discern the following states for the three plates of the Ortelius world map:

1 Typus Orbis Terrarum, plate 1

State 1 1570-1579 (from 1575 with bolt impressions in lower left corner)

State 2 1579-1584 crack somewhat mended, clouds reworked

State 3 1584-1585 date 1584 (or 1585) added to the right of Franciscus Hogenberg Sculpsit

112/I Typus Orbis Terrarum, plate 2

State 1 1586 unsigned, slightly smaller than plate 1, bordering clouds retained, dated 1586

State 2 1587-1589 as State 1 but without date

State 3 1588-1589 as State 2 but without corrected coastline of South America

113 Typus Orbis Terrarum , plate 3

State 1 1588-1612 medallions in corners, geographically revised, dated 1587

State 2 Le Maire Strait added, date removed

Another case of damage through use, this time with no repair attempted, is the plate of the African continent. From 1602 onwards the part of the copperplate for the lettering Africae Tabula Nova in the main cartouche began to crack. The later the print, the clearer these cracks become. Obviously, such unintended 'states' can be used to date maps just as succesfully as purposeful alterations although they are not formally recognised as new states.

Clearly, states constitute an undispensable tool for dating maps. Such information allows loose maps to be linked to specific editions. However, this sounds simpler than it turns out to be. it is my firm conviction that a more meticulous and systematic analysis than the customary informal analysis by eye (i.e. perhaps by computerised flatbed image scanning) would reveal many more states of each plate than have been identified so far.

Rather than showing wat the Romans knew of the world, this map shows the Roman empire itself. The medallions in the top corners show the legendary founders Romulus and Remus, the three at the lower right corner the lineage of the subsequent Roman kings (double circles) and their wives (single circles), based on thi historical writings of Livius, Dionysius and Plutarchus.

This map shows the area where Alexander the Great made his conquests, beginning in Egypt, where the Ammon-Jupiter oracle (see lower left) welcomed him as "Son of Zeus" and predicted a great future for him. The numerous cities in Persia called Alexandria which he founded are also shown.

| Regular atlas maps | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. |

Name |

period of usage |

numbers printed |

remarks |

| 1. | Typus Orbis Terrarum | 1570L–1584L | 3250 | |

| 2. | Americae | 1570L–1575L | 1675 | |

| 3. | Asiae | 1570L–1574L | 1575 | |

| 4. | Africae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 5. | Europae | 1570L–1581F | 3025 | |

| 6. | Angliae, Scotiae & Hiberniae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 7. | Regni Hispaniae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 8. | Portugalliae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 9. | Galliae | 1570L–1603L | 5650 | |

| 10. | Biturgum-Limaniae | 1570L–1612S | 7200 | not in 1598D |

| 11. | Caletensum-Veromandorum | 1570L–1598D | 4450 | |

| 12. | Galliae-Narbonensis-Sabaudiae | 1570L–1581F | 3025 | |

| 13. | Germaniae | 1570L–1602G | 5350 | |

| 14. | Germaniae Inferioris | 1570L–1606E | 5950 | |

| 15. | Gelriae, Cliviae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | not in 1592L and some in 1595L |

| 16. | Brabantiae | 1570L–1592L | 4150 | |

| 17. | Flandriae | 1570L–1575L | 1675 | |

| 18. | Zeelandicarum | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 19. | Hollandiae Catthorum | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 20. | Oost en West Friesland | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 21. | Daniae Regnum | 1570L–1581F | 3025 | |

| 22. | Thietmarsiae-Prussiae | 1570L–1581F | 3025 | |

| 23. | Saxoniae-Misniae-Thrungiae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 24. | Franconiae-Osnabrugensis | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 25. | Regni Bohemiae | 1570L–1612S | 4150 | |

| 26. | Silesiae | 1570L–1592L | 4150 | |

| 27. | Austriae | 1570L–1592L | 4250 | also in 1598D used side by side with 135/IV in 1595L |

| 28. | Salisburgensis | 1570L–1595L | 4250 | |

| 29. | Typus Vindelicae | 1570L–1573G | 1250 | |

| 30. | Bavariae-Wirtembergensis | 1570L–1581F | 2875 | |

| 31. | Helvetiae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 32. | Italiae | 1570L–1581F | 2875 | |

| 33. | Ducatus Mediolanensis | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 34. | Pedemontana | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 35. | Como-Romae-Friuli | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 36. | Thusciae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 37. | Regni Napolitanie | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 38. | Insularum Aliquot | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 39. | Cyprus-Candia | 1570L–1581F | 2875 | |

| 40. | Graeciae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 41. | Sclavoniae-Croatiae-Carniae | 1570L–1612S | 7225 | not in 1573D |

| 42. | Hungariae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 43. | Transylvaniae | 1570L–1575L | 1675 | |

| 44. | Poloniae | 1570L–1595L | 4250 | used side by side with 135/IV in 1595L |

| 45. | Septentrionalium Regionum | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 46. | Russiae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 47. | Tartariae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 48. | Indiae Orientalis | 1570L–1612S | 7025 | not in 1589F |

| 49. | Persici | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 50. | Turcii Imperii | 1570L–1575L | 1675 | |

| 51. | Palestinae | 1570L–1575L | 1675 | |

| 52. | Natoliae-Aegypti-Cartaginis | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 53. | Barbariae | 1570L–1612S | 7300 | |

| 53/I. | Hannoniae | never regularly in atlas |

5 copies known with date 1572, one without date | |

| 54. | Scotiae | 1573GI–1612S | 6275 | |

| 55. | Angliae | 1573GI–1602L | 4625 | also in 1606E |

| 56. | Cambriae Typus | 1573GI–1612S | 6275 | |

| 57. | Hiberniae | 1573GI–1603L | 3925 | |

| 58. | Mansfeldiae | 1573GI–1612S | 5850 | |

| 59. | Thuringiae-Misniae | 1573GI–1612S | 6025 | |

| 60. | Moraviae | 1573GI–1612S | 6025 | |

| 61. | Basilensis-Suaviae | 1573GI–1612S | 6175 | not in 1598D |

| 62. | Rhetiae-Goritiae | 1573GI–1612S | 6175 | not in 1598D |

| 63. | Fori Iulii | 1573GI–1612S | 6175 | not in 1598D |

| 64. | Patavini-Apuliae | 1573GI–1592L | 3825 | also in 1598D, 1598F |

| 65. | Senensis-Corsica-Ancona | 1573GI–1612S | 6275 | |

| 66. | Cypri Insulae | 1573GI–1612S | 6275 | |

| 67. | Carinthiae-Histriae-Zarae | 1573GI–1612S | 6275 | |

| 68. | Pomeraniae-Livoniae-Oswiec. | 1573GI–1612S | 6275 | |

| 69. | Presbiteri Johannis | 1573GI–1612S | 6275 | |

| 70. | Bavariae | 1573LI–1612S | 6100 | |

| 71. | Illyricum | 1573LI–1612S | 6000 | not in 1598D |

| 71/I. | Asiae | 1575L–1612S | 5625 | |

| 72. | Hispaniae Nova | 1579LII–1612S | 5875 | |

| 73. | Culicaniae, Hispaniolae, Cub. | 1579LII–1612S | 5875 | |

| 74. | Hispalensis Conventus | 1579LII–1612S | 5875 | |

| 75. | Pictonum | 1579LII–1612S | 5875 | |

| 76. | Anjou | 1579LII–1612S | 5775 | not in 1598D |

| 77. | Picardiae | 1579LII–1612S | 5875 | |

| 78. | Burgundiae | 1579LII–1612S | 4275 | not in 1589G, 1598D, 1603L, 1612I, 1612S |

| 79. | Lutzemburgensis | 1579LII–1612S | 5875 | |

| 80. | Namurcum | 1579LII–1612S | 5875 | |

| 81. | Hannoniae | 1579LII–1581F | 1450 | |

| 82. | Artois | 1579LII–1584F | 1725 | |

| 83. | Frisia Occidentalis | 1579LII–1612S | 5875 | |

| 84. | Frisiae Orientalis | 1579LII–1592L | 2725 | |

| 85. | Westphaliae | 1579LII–1612S | 5875 | |

| 86. | Hassiae-Holsatiae | 1579LII–1592L | 2725 | also in 1598F |

| 87. | Burghaviae-Waldeccensis | 1579LII–1612S | 5775 | not in 1598D |

| 88. | Wirtenberg Ducatus | 1579LII–1612S | 5775 | not in 1598D |

| 89. | Veronae Urbis | 1579LII–1612S | 5775 | not in 1598D |

| 90. | Agri Ceremonensis | 1579LII–1612S | 5775 | not in 1598D |

| 91. | Ungariae Loca | 1579LII–1612S | 5775 | not in 1598D |

| 92. | Turcii Imperii | 1579L–1612S | 5625 | |

| 93. | Palestinae | 1579L–1592L | 2725 | |

| 93/I. | Americae | 1589L–1584L | 1575 | |

| 93/II. | Flandria | 1579L–1589G | 2375 | also in some 1592L |

| 93/III. | Transilvania | 1579L–1612S | 5625 | |

| 93/IV. | Valentiae | none | only one copy known | |

| 94 . | Bavariae-Argentoratensis | 1584LIII–1612S | 4425 | |

| 95. | Acores | 1584LIII–1612S | 4425 | |

| 96. | Burgundiae Inferioris | 1584LIII–1612S | 4075 | not in 1598D, 1602S |

| 97. | Chinae | 1584LIII–1612S | 4425 | |

| 98. | Candia-Archipelagi | 1584LIII–1612S | 4425 | |

| 99. | Carpetaniae-Guipuscoae | 1584LIII–1612S | 4425 | |

| 100. | Leodiensis | 1584LIII–1595L | 1575 | |

| 101. | Daniae-Oldenburg | 1584LIII–1612S | 3975 | also with 109, 130 |

| 102. | Perusini Agri | 1584LIII–1612S | 4325 | not in 1598D |

| 103. | Peruviae-Florida-Guastecan | 1584LIII–1612S | 4425 | |

| 104. | Prussiae | 1584LIII–1595L | 1575 | |

| 105. | Romaniae | 1584LIII–1612S | 4325 | not in 1598D |

| 106. | Terra Sancta | 1584LIII–1612S | 4425 | |

| 107. | Valentiae | 1584LIII–1612S | 4325 | not in 1598D |

| 108. | Gallia Narb.-Sabaud.-Venux. | 1584LIII–1612S | 4425 | |

| 109. | Holsatiae-Rugiae | 1584LIII–1612S | 4425 | also with 101, 86 |

| 110. | Europae | 1584L–1612S | 4425 | |

| 111. | Hannoniae | 1584L–1612S | 4175 | not in 1602G |

| 112. | Italiae | 1584L–1612S | 4425 | |

| 112/I. | Typus Orbis | 1588S | 300 | used side by side with 113, 1587–1589 |

| 113. | Typus Orbis | 1587F–1612S | 3850 | |

| 114. | Americae | 1587F–1612S | 4150 | |

| 115. | Artesia | 1587F–1612S | 3800 | not in 1598D, 1602G |

| 116. | Burgundia Comitatus | 1589G & 1603L | 450 | |

| 116/I. | Angliae, Scotiae et Hiberniae | 1589 | composite | few noted by A. Kelly |

| 117. | Aprutti | 1590LIV–1612S | 3450 | not in 1598D |

| 118. | Brandenburgensis | 1590LIV–1612S | 3550 | |

| 119. | Bresciano | 1590LIV–1612S | 3450 | not in 1598D |

| 120. | Ischia | 1590LIV–1612S | 3550 | |

| 121. | Islandia | 1590LIV–1612S | 3200 | not in 1598F, 1602G |

| 122. | Lotharingiae | 1590LIV–1612S | 3550 | |

| 123. | Braunswicensis-Norimbergae | 1590LIV–1612S | 3550 | |

| 124. | Maris Pacifici | 1590LIV–1612S | 3550 | |

| 125. | Flandria | 1592L–1612S | 3450 | |

| 126. | Brabantiae | 1592L–1612S | 3450 | |

| 126/I. | Gelriae Cliviae | 1592L | 300 | also in some 1595L |

| 127. | Cenomanorum-Neustria | 1595LV–1612S | 3050 | not in 1598F, 1598D |

| 128. | Provinciae | 1595LV–1612S | 3150 | not in 1598D |

| 129. | Hennebergensis-Hassiae | 1595LV–1612S | 3050 | not in 1598F, 1598D also with 86 |

| 130. | Daniae-Cimbriae | 1595LV–1612S | 3150 | not in 1598D, also with 101 |

| 131. | Patavini-Tarvisini | 1595LV–1612S | 3050 | not in 1598F, 1598D |

| 132. | Florentini | 1595LV–1612S | 3150 | not in 1598D |

| 133. | Apuliae-Calabriae | 1595LV–1612S | 3050 | not in 1598F, 1598D |

| 134. | Iaponiae | 1595LV–1612S | 3250 | |

| 135. | Fessae et Marocchi | 1595LV–1612S | 3250 | |

| 135/I. | Frisiae Orientalis | 1595L–1612S | 3150 | |

| 135/II | Silesiae | 1595L–1612S | 3150 | |

| 135/III. | Gallia | none | 2? | never regularly included, cartouche from Mercator, Zeelandica |

| 135/IV. | Poloniae Lithunaiae | 1595L–1612S | 3050 | used side by side with 44 in 1595L |

| 135/V. | Salisburgensis | 1595L–1612S | 3050 | used side by side with 28 in 1595L |

| 135/VI. | Palestinae | 1595L–1612S | 2550 | not in 1598F, 1602S, 1602G |

| 136. | Isle de France | 1598F–1612S | 2850 | |

| 137. | Tourraine | 1598F–1612S | 2850 | |

| 138. | Blaisois-Lemovicum | 1598F–1612S | 2850 | |

| 139. | Caletensium-Veromanduorum | 1598F–1612S | 2850 | |

| 140. | Austriae | 1598F–1612S | 3050 | not in 1598D |

| 141. | Prussiae | 1598F–1612S | 2850 | |

| 141/I. | Leodiensis | 1598F–1612S | 2850 | |

| 142. | Burgundiae Ducatus-Comitatus | 1602S–1612S | 1300 | not in 1606E, 1608I |

| 143. | Angliae Regnum | 1603L | 300 | also in some 1602G, 1602S, 1608I, 1609L, 1610D |

| 144. | Cataloniae Principatus | 1603L–1612S | 1350 | not in 1606E |

| 145. | Reyno de Galizia | 1598D–1612S | 1750 | |

| 146. | 116 | 2050 | ||

| 147. | Deutschland | 1603L–1612S | 1650 | |

| 148. | Angliae et Hiberniae | 1606E–1612S | 1650 | |

| 149. | Irlandiae | 1606E–1612S | 1650 | |

| 150. | Gallia | 1606E–1612S | 1650 | |

| 151. | Limburgensis Ducatus | 1606E–1612S | 1650 | |

| 152. | Lacus Lemani | 1608I–1612S | 1050 | |

| 153. | Inferioris Germaniae | 1608I–1612S | 1050 | |

| 154. | Bononiensis-Vicentini | 1608I–1612S | 1050 | |

| 155. | Reipublicae Genuensis | 1608I–1612S | 1050 | |

| 156. | Parmae et Placentiae | 1608I–1612S | 1050 | |

| 157. | Ducatus Ferrariensis | 1608I–1612S | 1050 | |

| 158. | Romagna olim Flaminia | 1608I–1612S | 1050 | |

| 159. | Ducatus Urbini | 1608I–1612S | 1050 | |

| All regular atlas maps (174 plates) | about 730.000 | |||

| Parergon maps | ||||

| 1P. | Divi Pauli | 1579LII–1624P | 5875 | |

| 2P. | Romani Imperium | 1579LII–1624P | 5875 | |

| 3P. | Hellas, Graeciae Sophiani | 1579LII–1624P | 5625 | not in 1608I |

| 4P. | Aegyptus (North) | 1584LIII–1592L | 975 | |

| 5P. | Aegyptus (South) | 1584LIII–1592L | 975 | |

| 6P. | Belgii Veteris Typus | 1584LIII–1592L | 975 | |

| 7P. | Creta-Ins. Aliquot | 1584LIII–1624P | 4275 | not in 1598D |

| 8P. | Insularum Aliquot-Cyprus | 1584LIII–1624P | 4275 | not in 1598D |

| 9P. | Italiae Veteris Specimen | 1584LIII–1592L | 975 | |

| 10P. | Siciliae Veteris Typus | 1584LIII–1624P | 4275 | not in 1598D |

| 11P. | Tusciae Antiqua Typus | 1584LIII–1592L | 975 | |

| 12P. | Abrahami Patriarchae | 1590LIV–1595L | 400 | used side by side with 25P/I, 1592–1595 |

| 13P. | Aevi Veteris Typus | 1590LIV–1624P | 3800 | |

| 14P. | Africae Propriae Tabula | 1590LIV–1624P | 3700 | not in 1598D |

| 15P. | Brittanicae Insularum (North) | 1590LIV–1592L | 400 | |

| 16P. | Brittanicae Insularum (South) | 1590LIV–1592L | 400 | |

| 17P. | Pontus Euxinus | 1590LIV–1624P | 3700 | not in 1598D |

| 18P. | Gallia Vetus | 1590LIV–1602G | 1150 | not in 1598D |

| 19P. | Germaniae Veteris Typus | 1590LIV–1624P | 3700 | not in 1598D |

| 20P. | Hispaniae veteris Descriptio | 1590LIV–1624P | 3700 | not in 1598D |

| 21P. | Italia Gallica Cisalpina | 1590LIV–1624P | 3700 | not in 1598D |

| 22P. | Typus Chorographicus | 1590LIV–1624P | 3700 | not in 1598D |

| 23P. | Pannoniae et Illyrici | 1590LIV–1624P | 3700 | not in 1598D |

| 24P. | Tempe | 1590LIV–1624P | 3800 | |

| 25P. | Thraciae Veteris Typus | 1590LIV–1624P | 3700 | not in 1598D |

| 25P/I | Abrahami Patriarchae | 1592L–1624P | 3200 | used side by side with 12P, 1592–1595 |

| 26P. | Europam sive Celticam | 1595L–1624P | 3400 | not in 1598D |

| 27P. | Galliae Veteris Typus | 1595L–1624P | 3400 | not in 1598D |

| 28P. | Latium | 1595L–1624P | 3400 | not in 1598D |

| 29P. | Graecia Major | 1595L–1624P | 3400 | not in 1598D |

| 30P. | Daciarum Moesiarumque | 1595L–1624P | 3400 | not in 1598D |

| 31P. | Alexandri Magni | 1595L–1624P | 3400 | not in 1598D |

| 32P. | Aeneas Troiani Navigatio | 1595LV–1602G | 1250 | not in 1598D |

| 33P. | Daphne | 1595LV–1624P | 3400 | not in 1598D |

| 33P/I. | Belgii Veteris Typus | 1595L–1624P | 3300 | not in 1598D |

| 33P/II. | Italiae Veteris Specimen | 1595L–1624P | 3300 | not in 1598D |

| 33P/III. | Tusciae Antiquae Typus | 1595L–1624P | 3300 | not in 1598D |

| 34P. | Brittanicarum Insularum | 1595L–1624P | 3300 | not in 1598D |

| 35P. | Aegyptus Antiqua | 1595L–1624P | 3300 | not in 1598D |

| 36P. | Geographia Sacra | 1598F–1603L | 950 | |

| 37P. | Erythraeae sive Rubri Maris | 1598F–1608I | 1550 | |

| 38P. | Argonautica | 1698F–1624P | 3150 | |

| 39P. | Scenographia Escoriali | 1601L–1624P | 3050 | |

| 39PI. | Gallia Vetus | 1603L–1624P | 2550 | |

| 39PII. | Aeneas Troiani Navigatio | 1603L–1624P | 2550 | |

| 39PIII. | Geographia Sacra | 1606E–1624P | 1950 | |

| 39PIV. | Erythraeae sive Rubri Maris | 1609L–1624P | 1350 | |

| 40P. | Ordines Sacri I | 1603L–1624P | 2550 | |

| 41P. | Ordines Sacri II | 1603L–1624P | 2550 | |

| 42P. | Lumen Orientalis | 1624P | 300 | |

| 43P. | Lumen Occidentalis | 1624P | 300 | |

| 44P. | Peutingerorum(I,II) | 1624P | 300 | separately issued 1598 |

| 45P. | Peutingerorum(III, IV) | 1624P | 300 | separately issued 1598 |

| 46P. | Peutingerorum (V, VI) | 1624P | 300 | separately issued 1598 |

| 47P. | Peutingerorum (VII, VIII) | 1624P | 300 | separately issued 1598 |

| All Parergon maps (55 plates) | about 143.000 | |||

| Total of all maps (228 plates) | about 873.000 | |||

But what about the development of texts in the Theatrum? Since most editions contain texts in Latin, which is no longer the language of science, this aspect has been neglected. Even Meurer has confined his search of sources for each plate to the Catalogus Auctorum2 and has not analysed the development of the text accompanying each plate in systematic detail. A text history, in some cases augmented by information on the paper watermark, is useful in dating maps. Texts and their development over various editions also provide insight into new information, new sources, and the nature of the feedback that Ortelius received from his customers and fellow cartographers.

Descriptions of various atlas editions in cartobibliographical literature such as Koeman's Atlantes Neerlandici8 raises the expectation that all exemplars of that edition are identical in texts as well as plates. However, inspection of two copies of what Koeman calls edition 1(A) of the Theatrum in the University Libraries of Amsterdam and Leiden 1(B) does not confirm this. The maps of "Flandria" turn out to derive from two different parallel plates, as also pointed out by Gittenberger: the cartouches differ at the middle in top and bottom area (see illustration)9. The Leiden exemplar shows a heart, whereas that of Amsterdam does not. Comparison of the texts between the Leiden exemplar and the Amsterdam exemplar yield considerable differences: in (A) the title of map 5 (Europe) is reset when compared with (B). In plate 8 (Portugalliae), 9 (Galliae), 34 (Pedemontanae), 35 (Como), 46 (Russiae), 47 (Tartariae) and 51 (Palestinae) the whole text is reset. Sometimes it is longer in (A), sometimes longer in (B).

How can this be and which of these exemplars from supposedly the same variant of the same edition came first? It is tempting to regard the version with the most text as the later one, as texts tend to grow in size over editions, but even this simple question cannot be answered as the first exemplar has more text in some cases than the later exemplar. Are these differences exceptional and restricted to this variant of the first edition, or is it the rule? In order to answer this question I decided to campare three exemplars of the 1595 Latin edition, the last one that Ortelius himselfproduced before his death in 1598. These are atlas 1803 A7 in Amsterdam University Library, a copy from the Florence Military Library that has appeared in facsimile10 and atlas 1802 A6 from Amsterdam University Library.

Differences between all three exemplars are numerous: for 1803 A7 left-over sheets dating back to the 1584 Latin and even to the 1575 Latin edition were used. Text sheets differ not only in type and length but also in order. The order of the Parergon maps in the Florence exemplar is erratic in spite of its old binding. Differences in the maps and texts between exemplars of one edition turn out to be the rule rather than the exception.

Of all exemplars (about ninety) of the Theatrum offered for sale and described in detail by the major auction houses between 1980 and 1992 almost half do not conform to the Koeman descriptions. They may contain maps or a nomenclature not called for, or lack one that should have been included, display other text sections which are inconsistently included or excluded, or contain Additamenta included in an unpredictable manner (one 1570 Latin edition offered recently contains two identical 1574 Latin I Additamenta bound up with it) or editions may contain maps from de Jode's Seculum Orbis Terrarum or Braun and Hogenberg's Civitates Orbis Terrarum etc.

A typical example to further demonstrate variability between exemplars of the same edition is a composite atlas with a late binding acquired at Sotheby's, London, on April 23, 1987; it contains some maps from de Jode's Speculum … and a few manuscript maps inserted at the appropriate places. It also contains, in mutilated form, the mysterious 71/II Hannonia map, mentioned in Denucé4 (Volume I p. 36 and Volume II p.41 ff) which never appeared regularly in Theatrum editions due to lack of privilegio (cf. Meurer11). Title-page and colophon qualify this atlas as a 1573 Latin exemplar, but it also has maps with page numbers from the 1573 Latin I Additamentum inserted at the appropriate places. Moreover, it contains both the early Bavaria map 29: "Typus Vindelicae" (1570 Latin-1573 German edition) and the later map 70: Bavaria (1573 Latin Additamentum I-1612 Spanish edition).

It seems that the notion "edition" needs a redefinition in view of this data. When we buy a book today we expect to obtain a physical object which is identical with the same edition of that book bought by everyone else. But clearly this has not always been the case. For early atlases like the Theatrum the definition of unstable editions is needed. This becomes better understood when the production methods of thge atlas are examined.

Maps were printed intaglio from copperplates on which the information was engraved by mirror image. Plates were inked, then wiped clean and the ink remaining in the copper grooves was transferred to the damp paper by applying high pressure from a roller. The resulting prints or pulls were hung up to dry. Texts were composed by setting individual letters in reverse order into rows forming the printed lines, and putting these one beneath another until the text of an entire page had been set. These rows of letters were then fixed on a page block, inked and block pressed on to the paper at relatively low pressure. In principle there is no reson why either text or map should be printed first but in practice there is a big difference: type could be removed from the page block after use and re-used for composing new texts whereas a copperplate is a more fixed, permanent medium. Individual letters used for typesetting represented a considerable investment for the printer and were always in high demand and short supply which is the reason it was not feasible to typeset an atlas in one go. Instead, typeset pages were broken up as soon as enough copies had been drawn from it in order to re-use the type for subsequent pages of text. Therefore, it was in the printer's interest to print the text sheets in sufficient numbers, and only to print the maps on verso as needed. An exception to this is the 1606 English edition.

The red sea, which in Ortelius rendering of classical knowledge extends along both sides of the Indian peninsula, does not derive its name from being red, but from Perseus' son Erythras (the red king) who was buried on some island in this sea. Note the relatively accurate representation of the Indian continent and the IndoChinese/Malaccan peninsula. The inset map shows the various places that Ulysses visited on his wanderings from Troy to his native Ithaca, as first described in Homer's Odysse. This new plate (39P/IV) is different from its predecessor (37P) in being slightly larger, and in having more text and a different cartouche.

The chance of there being an exactly equal number of sheets in one print run is small, particularly as some pulls would fail in quality and be discarded. This means that a new edition may contain old sheets that were left over from a previous printing with old texts and old plates, or with old texts and new plates. To complicate matters further, it might also contain new texts and old plates; in spite of the arguments above it was not uncommon to print some map plates on sheets without text in order to sell them individually. Some 50% of the loose Ortelius maps in my possession are without text on verso. Once a new edition was being prepared, old stockpiles of such sheets might be provided with texts and included in the new edition for economic reasons.

It is unlikely, in view of this, that all exemplars of a single issue of the Theatrum are exactly alike as regards plates and texts. When two versions of a plate were available side by side it is still possible that a mix up could occur and that an earlier issue appeared with the later plate or vice versa. This is what happened with the 1592 Latin which has the new Abraham plate (25P/I) with the background hachuring between the medallions going from lowr right to upper left. Similarly plate 2 and 3 of the world map (112/I and 113) co-existed for some time. 112/I occurs in the 1588 Spanish edition but also in the 1589 German edition in its first and second state, with a bulge in South America. The bulge was corrected on this plate but the impressions not included regularly in atlases. Plate 113, in which the bulge has been corrected and which features medallions rather than clouds in the corners, occurs in the 1587 French and 1589 German editions and is from then on used as the only world plate. For text, too, variations may be expected to be the rule rather than the exception.

The physical characteristics of a printer's shop at this time must also be taken into account in this argument. Even Blaeu's wellknown premises at the Bloemgracht in Amsterdamn, a century after Ortelius, produced its momumental output from premises measuring only 160 sq. metres (approx. 1600 sq.feet). Ortelius' Latin edition of the Theatrum was produced from the famous Plantin printing presses in Antwerp along with many others.10 The 300 or so piles of map and text sheets, each at least 200 sheets high, would be waiting to be bound in cramped conditions. The chances of mistakes being made when these sheets were collated for binding were high and this is what we found. In addition, atlases were often left unbound until the buyer had been consulted about the binding required. All this contributes to the instability of an edition.

On the basis of our findings we do not agree with Koeman's premise that an atlas edition may be regarded as the standard by which to compare other copies. Each copy of these manually produced atlases is unique and each edition will display a certain degree of instability in respect to other exemplars of that edition. The degree of instability of each Theatrum edition and of other early atlases produced in a similar manner (Meurer reports a similar instability amongst atlases by Sebastian Münster) can only be determined by comparing many exemplars of each edition. Fortunately, enough exemplars of each edition of the Theatrum still exist in order for us to do this.

References:

1 Marcel van den Broecke, "How rare is a map and the atlas it comes from? Facts and speculations on production and survival of Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum and its maps" in The Map Collector 36, pp.2-12.

2 Peter H. Meurer, "Fontes Cartographici Orteliani: das 'Theatrum Orbis Terrarum' von Abraham Ortelius und seine Kartenquellen', (Weinheim: VCH, 1991).

3 Robert W. Karrow, Mapmakers of the sixteenth century and their maps (Winnetka, Chicago: Speculum Orbis Press, 1993).

4 Jan Denucé, Oud-Nederlandsche kaartmakers in betrekking met Plantijn, (Amsterdam: Meridian Publishing Company, 1912).

5 Làszló Gróf, "Magyarország térképei az Ortelius atlas zokban" in Cartographica Hungarica 1 (1992) pp.26036.

6 Rodney W. Shirley, Early printed maps of the British Isles 1477-1650 (East Grinstead: Antique Atlas, 1991).

7 Rodney W. Shirley, The Mapping of the World: early printed world maps 1472-1700 (London: Holland Press, 1993).

8 C. Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici Vol. 3 (Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1969).

9 Personal communication.

10 A. Ortelius, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Facsimile of the 1595 edition (Firenze, Giunti, 1991).

11 Peter H. Meurer, "De verboden eerste uitgave van de Henegouwen-kaart door Jacques de Surhorn uit het jaar 1572 in Caert Thresoor 13 (3), 1994, pp. 81-87.

Acknowledgments:

This paper, which will also appear in a shortened form in Dutch Caert Thresoor, has benefited from comments by C. Koeman, D. de Vries, B. Buijnsters, R. Shirley, A. Kelly, L. Grof, F. Gittenberg, P. Meurer, G. Ritzlin and R. Karrow.